Bubbles in bread

Cereals such as wheat, maize and rice are the source of human civilisation and continue to feed the world; more than half of our food, globally, comes from cereals, either directly or via grains fed to animals for meat, milk and eggs. Of the cereals, wheat is the most important. Wheat is not the most abundant cereal; we produce more maize than any other cereal. Wheat does not feed the most people; rice feeds the most people. Wheat is not the most nutritious cereal; oats are the most nutritious cereal, and eating more porridge is one of the healthiest food choices you can make. But wheat is still the most important, in terms of its effects on human history, technology, politics, trade and international relations. The pre-eminence arises because wheat is unique in its ability to give us raised bread, due to its unique gluten proteins that allow formation of a dough that can retain the fermentation gases produced by yeast to give a highly aerated and palatable loaf. And we like the luxury of raised bread, and will shift our trade and social structures and technological development to deliver this uniquely appealing food. For this reason Jacob (1944) observed “Bread ruled over the ancient world; no food before or since exerted such mastery over men!”, while Socrates declared “No man qualifies as a statesman who is entirely ignorant of the problems of wheat.”

So (as I wrote in my History of Aerated Foods in the Bubbles in Food 2 book) wheat is the world’s most important food because it gives us bread; bread is the most important food, because of its bubbles; therefore bubbles are the world’s most important food ingredient! The logic is irrefutable!

But as ingredients go, bubbles are not as familiar and easy to understand as things like starch and protein and fats, which are well studied and understood by food chemists – hence bubbles have been called “the neglected ingredients”, as they are physical rather than chemical things. But chemical engineers are well placed to understand how bubbles behave, and hence to make a unique contribution to food studies and to improving the quality, variety and luxury of foods.

Bread is the most iconic aerated food, but there are many others – cakes, pastries, whipped cream, soufflés, mousses, popcorn, Swiss cheese, aerated chocolate, meringues, ice cream – and of course drinks – the head of beer or Coke or cappuccino, soft drinks and sparkling wine, including the iconic Champagne, popularly called Bubbly. Bubbles really are very versatile ingredients! A chemical engineering understanding of bubble behaviour in all these foods and drinks has a lot of potential to enhance and extend their use in the commercial and domestic settings to give us novelty and luxury.

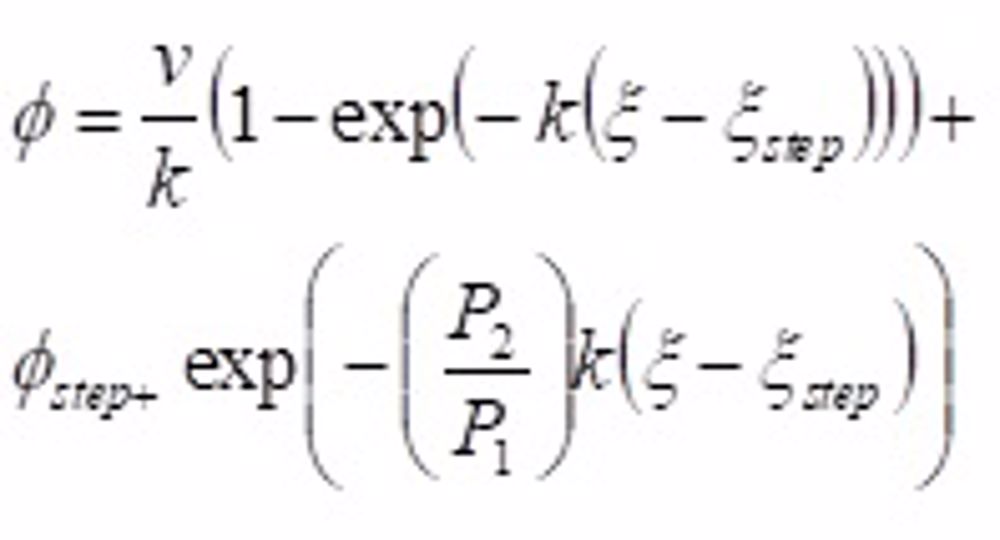

My own engagement with bubbles in food started in the Department of Chemical Engineering in Cambridge in 1987, when I embarked on my PhD on “The Aeration of Bread Dough during Mixing”. Bubbles in bread start out as bubbles in the dough, but understanding how the number and size of bubbles in the dough translate into the size and texture of the loaf has proved quite challenging, and continues to occupy me more than 30 years later. That interest has extended to bubbles in foods more generally and to issues of aeration dynamics during mixing (entrainment, disentrainment, break-up and coalescence of bubbles and how these relate to the gas content and bubble size distribution), bubble growth during rising and baking, how aerated structure relates to texture, and how these things are affected by ingredients such as bran in wholemeal breads. New insights have been gained, such as how the slow turnover of air during mixing limits oxygen availability for gluten development, by combining mathematical modelling with experimental work – classic chemical engineering approaches that allow new questions to be asked and new light to be sought.

But chemical engineering is also about bigger perspectives and interconnections. If bread is the world’s most important food, does it have relevance to pressing issues such as climate change, oil depletion and global health and well-being? Yes, in numerous and subtle ways! One of these is through the relevance of bread to the rise of biorefineries and their important contributions to alleviating these pressing global issues. The emergence of biorefineries now gives a context in which new foods ingredients, currently not commercially available to the food industry, could become affordable in the context of an integrated biorefinery. Such ingredients will contribute to the economic viability of biorefineries, and hence help to usher them in such that the world can begin to benefit from their contributions. And the first of those ingredients are likely to be healthy fibre-based ingredients that improve the quality and nutritional value of bread, by enhancing its bubble structure. In such ways does bread, and its bubbles, link us back to our shared history and forward to our shared future.