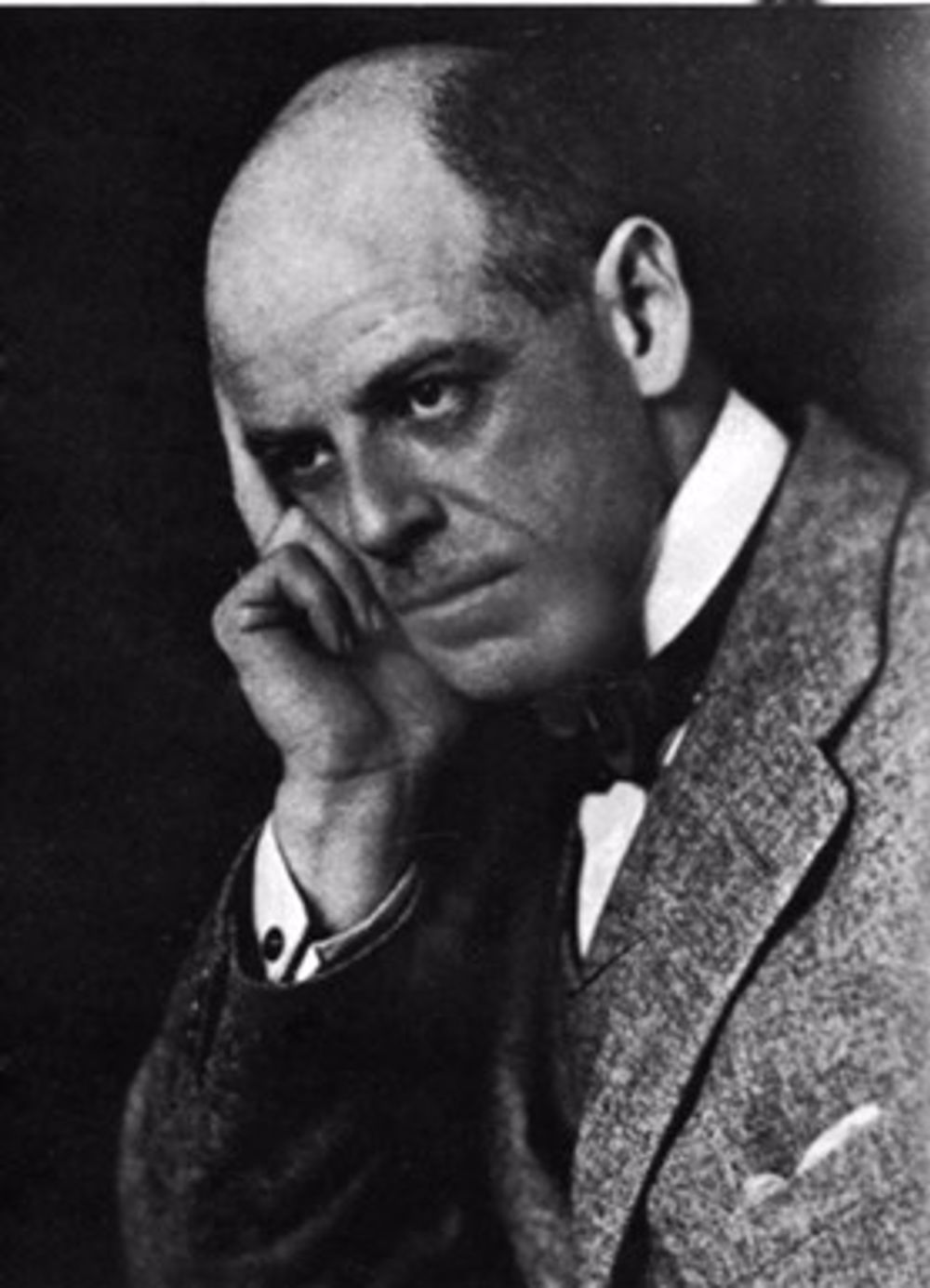

K B Quinan

In 1917, King George V instituted a new award for outstanding achievement - the Order of Companions of Honour. Amongst those gazetted was Mr. K B Quinan, an American Citizen, previously resident in South Africa, his citation read for “special work in connection with the Explosives Supply Department of the Ministry of Munitions.” It was special indeed - it was chemical engineering!

At the start of the Great War, great concern had been expressed about the supply of munitions, an issue which led to the Great Shell Crisis of 1915. It was recognised that major new factories would have to be built to supply the needs of the troops. In the UK there were few who had such experience and a general dearth of any who would describe themselves as chemical engineers, but it was to one such that the call went out, relayed by cable to the 36-year-old Kenneth Bingham Quinan in Somerset West in the Cape. The same day KBQ (as he was always known) set sail to England. Quinan was self-taught having succeeded his uncle as General Manager of the de Beers’ Cape Explosives Company works (the largest in the world at the time), built to break the monopoly of the Nobel Dynamite Trust.

The appointment was inspired, a formidable organiser and hands on designer, KBQ had, as Arthur Conan Doyle put it ‘the drive of a steam piston.’ Within 100 days a major TNT plant had been built and put into operation at Oldbury, and distillation units for toluene production from Borneo crude had been dismantled in Rotterdam and moved to Avonmouth and Barrow-in-Furness. More engineers and chemists were brought in from the Empire - notably Australia and South Africa.

At the same time Quinan was designing the two great munitions factories for propellants and high explosives that were central to the national ambition to increase supplies to the troops, these factories were sited on the Cheshire/Welsh border at Queensferry/Sandycoft and across the Solway Firth at Gretna. Quinan was more than a great organiser in time of war, he was intimately involved in the design of every facet of the plants and brought his own patented inventions into the processes. Every design blueprint, now in the National Archives, was signed off individually by KBQ.

The statistics regarding the plants and their production represent a scaling up that had seemed inconceivable before KBQ joined the war effort.

But Quinan saw beyond the war, he saw his designs and his manner of operation as a ‘great educational enterprise,’ his designs for all facets of the plants were to be taken up and edited by McNab and Cremer (both later to be Presidents of IChemE) and published after the war as instructional materials for a new generation of engineers. Indeed, the impetus to establish an Institution of Chemical Engineers was led by those who had worked with KBQ in the munitions effort in the war.

Without the work of embryo chemical engineers in the war effort, victory would have been impossible and the recognition of chemical engineering as a major distinctive branch of the engineering profession would have been delayed for decades. The centenary we now mark owes an immeasurable debt to KBQ.