Colin Putt - Chemical Engineer and adventurer

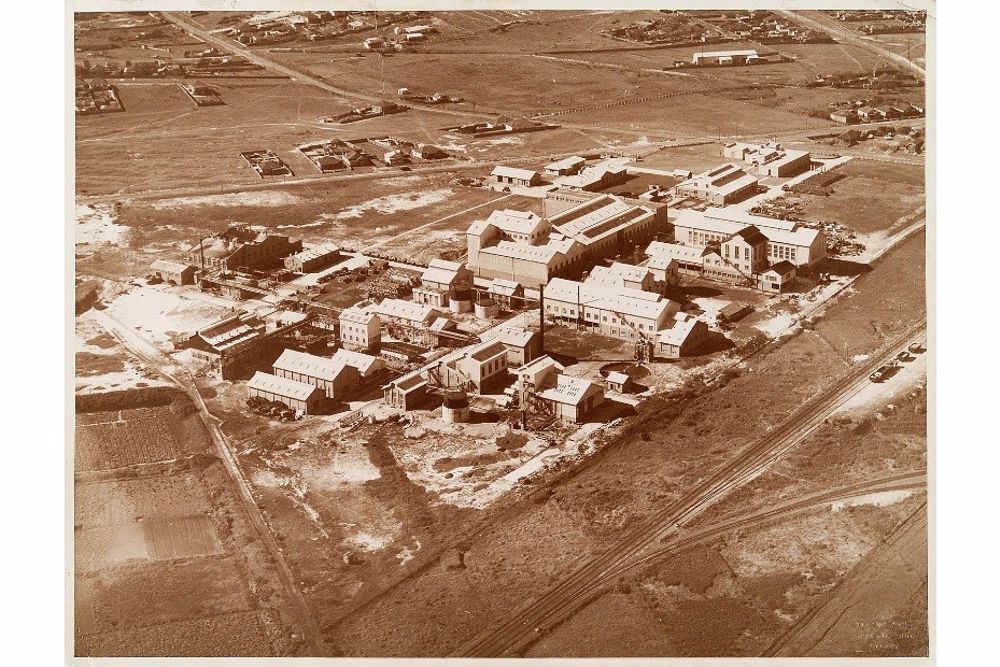

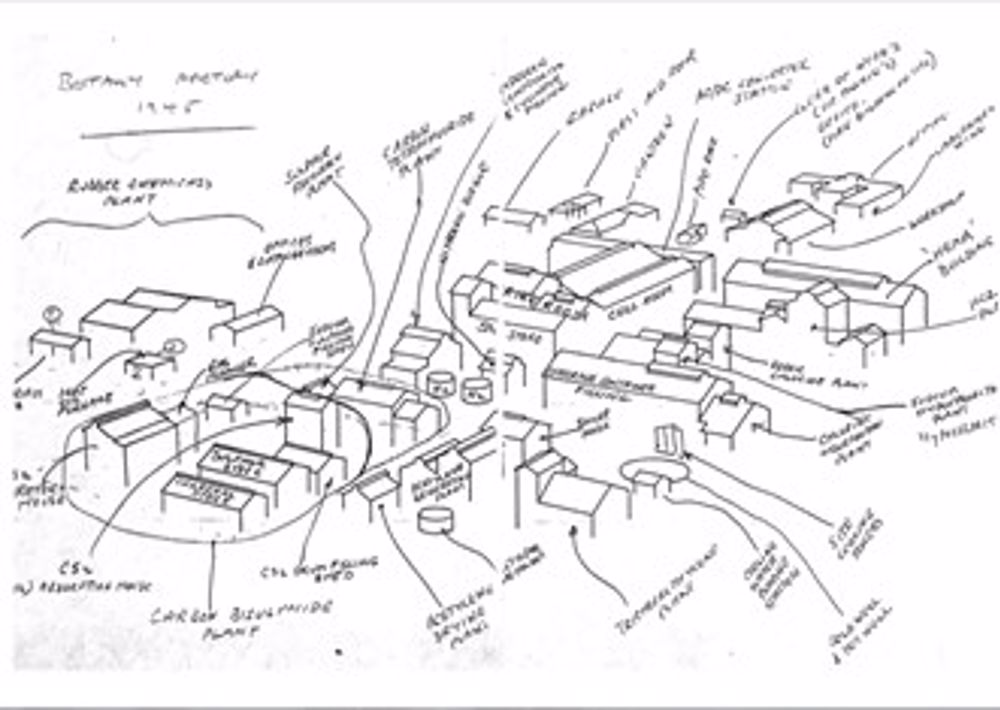

Imperial Chemical Industries Australasia and New Zealand (ICIANZ) evolved to meet demand for explosives from Australian gold and minerals miners during the latter part of the 19th century, with the company expanding into petrochemicals and plastics following the 2nd world war. ICIANZ quickly realised the benefits of a high-quality research laboratory which was built at Ascot Vale in Victoria in the 1950s and was staffed by chemists and chemical engineers. This led to the development of processes such as the oxychlorination of ethylene to produce vinyl chloride monomer, which then could be polymerised to polyvinyl chloride (PVC). This process helped justify the construction of a world scale ethylene cracker at the Sydney Botany site in the early 1980s. As demand for petrochemical products grew in Australia it became imperative for companies like ICANZ to hire bright young chemical engineers such as Colin Putt, to meet customer expectations and to improve process safety, which was only just beginning to receive the attention it deserved.

Colin Putt was born in New Zealand in 1926 into a family “addicted to engineering, rowing, sailing and snow sports”. He studied chemical engineering in Auckland because it “might be exciting and it certainly was.” After graduating, Colin joined ICIANZ’s electrolytic mercury cell (chloralkali) plant at Botany in 1950 to work on process safety at a plant which was not yet on top of its start-up processing problems and environment protection was yet to be a consideration. Putt notes that the plant had “frequent fires, explosions, toxic gas escapes, injuries and occasional deaths.” Rumour had it that for one to get ahead in the company it was necessary to be involved in, preferably responsible for, a big disaster. When an advantageous position presented itself, then the Directors might say “Putt, I’ve seen that name somewhere, let’s give him the job.” Thus in 1956 Colin Putt found himself in ICI’s London head office studying secret processes, where he learnt a lot about rock climbing, rugger songs and a little about secret processes.

Back in Australia Colin was asked to design, build, and commission a new plant to make up a shortfall of hydrochloric acid promised by a great salesman in just 5 weeks! By developing a new kind of process design, innovative design methods, new construction techniques and living in a shed at the works, he got it going in five weeks and two days. Colin remembered this experience as “my first big adventure, I stuck my neck right out and got away with it.”

In 1960, as Putt tells it, he ran into Sir Edmund Hillary (1st ascent of Mt Everest) and Norman Hardie (1st ascent of Mt Kangchenjunga) at Sydney airport, and they asked him if he would head an expedition. “I replied yes, where is it going to (to answer like this you had to have the right wife and right employer and I had both).” Although this trip did not proceed Colin Putt had a lifetime of expeditions culminating in him being named Australian Adventurer of the year in 1986.

Putt’s career blossomed in ICI where he demonstrated great resourcefulness, while expanding his experience as a mountaineer and adventurer. In 1972 he was shipped off to London to manage an engineering research group for two years, not for his academic prowess, but as a hatchet man “the bastard from far away” to implement drastic changes to the company’s research organisation. His weekends were spent rock climbing, mountaineering in Norway, or sailing in Scottish lochs. After three years he was asked to stay permanently, but he decided the place was too badly over-run with Poms and he returned to Australia in 1975 assigned to dealing with rising concerns about the toxic impact of vinyl chloride monomer (VCM). While the company had no cases of hemangiosarcoma of the liver at that time, a lot of money was spent on reducing VCM leaks by an order of magnitude to meet allowable exposure limits. Colin sat down with the accountants and discovered that the leak reductions paid for themselves in two years due the value of savings in monomer.

In 1980 Putt was sent to the Barossa Valley in South Australia to manage ICI’s solar salt fields, allocating priority to the vineyard on the company owned property and arranging for the grapes to be harvested for wine production by Saltrams, which included a very drinkable Shiraz controlled by the Alkali Chemical Group for distribution to their clients or purchased by the staff.

Resources:

- The Chemical Industry and the Australian Contributions to Chemical Technology published by the Australian Academy of Technological Sciences and Engineering in 1988 by Jan Kolm

- Colin Putt’s personal notes for his speech TALK FOR OLD ADVENTURERS’ LUNCH. MY LIFE OF ADVENTURE (& MISADVENTURE) to accept the Australian Geographic Society’s Lifetime of Adventure medallion on June 19th, 2013

- Obituary Vale Colin Putt: inspirational engineer and adventurer 1926-2016 Sydney University Engineering facility