How Australia Won the Battle of Kokoda

My early memories as a graduate engineer at Monsanto’s West Footscray plant in Melbourne included wandering into the old brick building with expansive glass windows, which housed the acetylsalicylic acid or aspirin plant, with its wide range of processing equipment, including glass lined batch reactors, centrifuges, batch pan and fluidised bed dryers and tablet presses. Later I remember walking through the building with research chemist Mike, who would inevitably grab a sample of raw aspirin from a product bin to ward off a threatening migraine. What I didn't realise was the role this plant played in the dark days of the war in the Pacific.

One lesson emerges more clearly than almost any other from past warfare. That lesson is that disease may be many times more destructive than the clash of armed forces. Diseases such as typhus, plague, dysentery and malaria have often, throughout history, decided the course of a campaign. Until the early 1930s there were no treatments for bacterial infections resulting in large death rates in the community every year from pneumonia, meningitis, dysentery and streptococcal infections. During the 1930s German chemists developed Prontosil the first of a class of ‘sulpha’ drugs all based on the sulphanilamide molecule. These drugs demonstrated astonishing successes in the treatment of bacterial infections and were being widely used by many countries on the outbreak of the second world war.

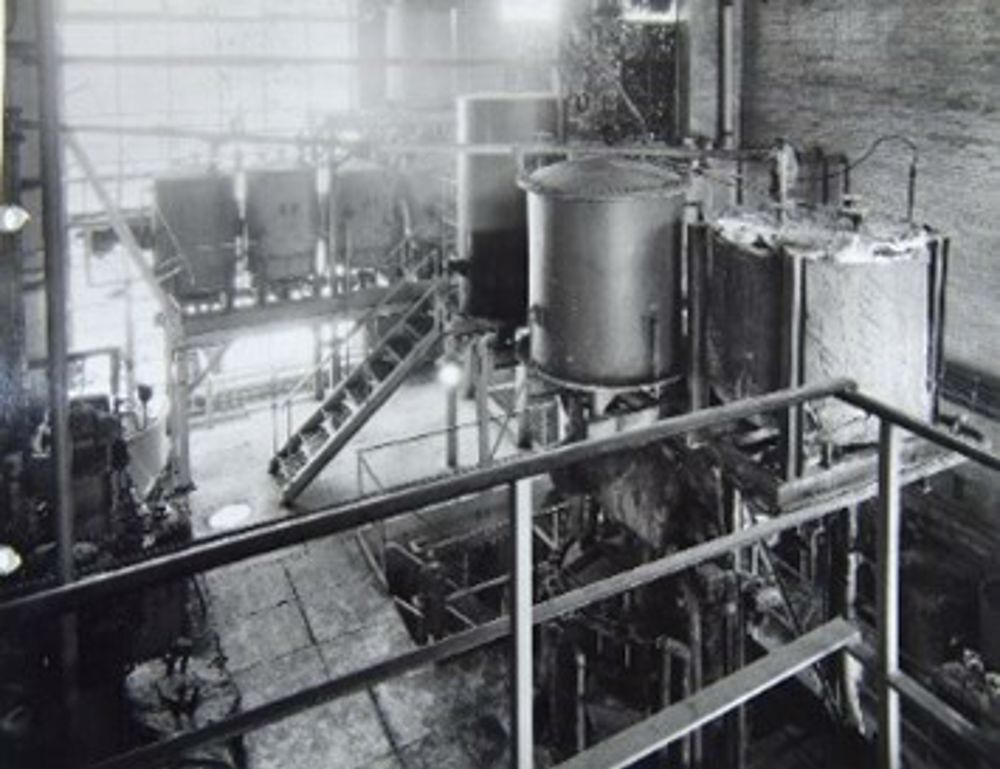

In 1942 Australia was entirely dependent on imported sulpha drugs and as Monsanto was already manufacturing Aspirin at West Footscary it was no surprise when the Australian government’s Medical Equipment Control Committee (MECC) requested Monsanto to locally manufacture the sulpha drug sulphanilamide for use by the army. Monsanto’s chemical engineers and chemists at West Footscray set about developing a process for synthesising sulpha drugs at the required quality and capacity. They utilised existing processing plant supplemented by new equipment specified and designed by the local engineering team and substantially fabricated in Australia.

Within 9 months the first batches of sulphanilamide were ready for conversion to tablets thanks to a tireless effort by Monsanto’s team. Almost immediately the plant was then modified to produce another sulpha drug, sulphaguanidine which was synthesised from the more toxic sulphanilamide. Sulphaguanidine was in high demand for its effectiveness against bacillary dysentery, which was rife in the jungles of New Guinea. Installation of equipment designed by the local engineering team to produce this drug began in mid-October 1942. Activities proceeded at fever pitch and once again by working around the clock the engineering team was able to deliver the first 100lbs of purified drug for shipment to the army to schedule in the first week of November. The Australian army was first to adopt sulphaguanidine as a specific drug for dysentery. In the opinion of Sir Alan Newton (consulting surgeon to the Australian Army during WW2) “If this drug had not been available there might well have been a very different end to the battle of Kokoda”.

From November 1942 onward the drug was delivered to Australian armed forces at a rate of up to 500lbs a week. Production was increased further in 1944 to meet demands of the British forces in Burma and India. All up a total of about 200 tons of these drugs were supplied by Monsanto with its West Footscray plant being the largest private enterprise drug manufacturer in Australia during the war.

While sulpha drugs are still in use for some applications today, penicillin quickly superseded them as the antibiotic of choice and Monsanto stopped making sulpha drugs in the mid-1950s. Aspirin production continued for another 30 years at West Footscray, accounting for the bulk of Australian demand.

Resources:

Second World War Official Histories, Volume V - The Role of Science and Industry (1st Edition , 1958) by David Paver Mellor, Chapter 26 - Vitamins, Drugs and Other Fine Chemicals

The Chemical Industry and the Australian Contributions to Chemical Technology published by the Australian Academy of Technological Sciences and Engineering in 1988 by Jan Kolm

Monsanto Australia Limited Internal Brochure, printed in the early 1980s “It Started With….”

Weary The Life of Sir Edward Dunlop by Sue Ebury, Published by Viking Australia, 1994

Photos of the Sulpha Drugs production facilities at West Footscray during the 2nd World War

Faith, Hope & $5,000 The Story of Monsanto, The Trials and Tribulations of the First 75 Years. by Dan J. Forrestall, Published by Simon and Schuster New York, 1977.